İzmir, historically Smyrna, is the third most populous city of Turkey and the country's largest port after İstanbul. It is located in the Gulf of İzmir, by the Aegean Sea. It is the capital of İzmir Province. The city of İzmir is composed of 9 metropolitan districts. These are Balçova, Bornova, Buca, Çiğli, Gaziemir, Güzelbahçe, Karşıyaka, Konak, and Narlıdere. Each district, and generally the neighborhoods within it, possesses distinct features and a particular temperament (for detailed information, see the articles on these districts). The 2000 population of this urban zone was 2,409,000 and the 2005 estimate is 3,500,000.

İzmir is the inheritor of almost 3,500 years of urban past, and possibly up to that much more in terms of advanced human settlement patterns. It is Turkey's first port for exports and its free zone, a Turkish-U.S. joint-venture established in 1990, is the leader among the twenty that Turkey counts. Its workforce, and particularly its rising class of young professionals, concentrated either in the city or in its immediate vicinity (such as in Manisa), and under either larger companies or SME's, affirm their name in an increasingly wider global scale and intensity [1]. İzmir is widely regarded as one of the most liberal Turkish cities in terms of values, ideology, lifestyle, dynamism and gender roles. It is a stronghold of the Republican People's Party.

Names and etymology

Names and etymology

Undisturbed wild horses roam in Mount Yamanlar overlooking İzmir and the neighboring Mount Sipylus (Mount Spil) National Park.

The name of a locality called Ti-smurna is mentioned in some of the Level II tablets from the Assyrian colony in Kültepe (first half of the 2nd millennium B.C.), with the prefix ti- identifying a proper name, although it is not established with certainty that this name refers to İzmir.[3] Some would see in the city's name a reference to the name of an Amazon called Smirna.

The region of İzmir was situated on the southern fringes of the "Yortan culture" in Anatolia's prehistory, the knowledge of which is almost entirely drawn from its cemeteries [4], and in the second half of the 2nd millennium B.C., in the western end of the extension of the yet largely obscure Arzawa Kingdom, an offshoot and usually a dependency of the Hittites, who themselves spread their direct rule as far as the coast during their Great Kingdom. That the realm of the local Luwian ruler who legated the 13th century B.C. Kemalpaşa Karabel rock carving at a distance of only 50 km from İzmir was called Mira may also leave ground for association with the city's name. [5]

The oldest rendering in Greek of the city's name we know is the Aeolic Greek Μύρρα Mýrrha, corresponding to the later Ionian and Attic Σμύρνα (Smýrna) or Σμύρνη (Smýrnē), both presumably descendants of a Proto-Greek form *Smúrnā. It would be linked to the name of the Myrrha commifera shrub, a plant that produces the aromatic resin called myrrh and is indigenous to the Middle East and northeastern Africa. The Romans took this name over as Smyrna which is the name still used in English when referring to the city in pre-Turkish periods. The name İzmir (Ottoman Turkish: إزمير İzmir) is the modern Turkish version of the same name.

In Greek it is Σμύρνη (Smýrni), Իզմիր (Izmir) in Armenian, Smirne in Italian, and Izmir (without the Turkish dotted İ) in Ladino.

In English, the city was called Smyrna until the early twentieth century and has been called İzmir since. In written Turkish it is spelled with a dotted İ at the beginning.

İzmir is nicknamed "Occidental İzmir" or "The Pearl of the Aegean".

İzmir is the inheritor of almost 3,500 years of urban past, and possibly up to that much more in terms of advanced human settlement patterns. It is Turkey's first port for exports and its free zone, a Turkish-U.S. joint-venture established in 1990, is the leader among the twenty that Turkey counts. Its workforce, and particularly its rising class of young professionals, concentrated either in the city or in its immediate vicinity (such as in Manisa), and under either larger companies or SME's, affirm their name in an increasingly wider global scale and intensity [1]. İzmir is widely regarded as one of the most liberal Turkish cities in terms of values, ideology, lifestyle, dynamism and gender roles. It is a stronghold of the Republican People's Party.

The city hosts an international arts festival during June and July, and the İzmir International Fair, one among the city's many fair and exhibition events, is held in the beginning of September every year. It is served by national and international flights through Adnan Menderes Airport and there is a modern rapid transit line running Southwest to Northeast. İzmir hosted the Mediterranean Games in 1971 and the World University Games (Universiade) in 2005. It currently has a running bid submitted to the BIE to host the Universal Expo 2015, which will be voted on in 2008. Modern İzmir also incorporates the nearby ancient cities of Ephesus, Pergamon, Sardis and Klazomenai, and centers of international tourism such as Kuşadası, Çeşme and Foça.

Despite its advantageous location and its heritage, until recently İzmir has suffered, as one author puts it, from a "sketchy understanding" in the eyes of outsiders. When the Ottomans took over İzmir in the 15th century they did not inherit compelling historical memories, unlike the two other keys of the trade network, namely İstanbul and Aleppo. Its emergence as a major international port as of the 17th century was largely a result of the attraction it exercised over foreigners, and the city's european orientation. [2] Very different people found İzmir attractive over the ages and the city has always been governed by fresh inspirations, including for the very location of its center, and is quick to adopt novelties and projects. Nevertheless, its successful completion of the 2005 Universiade games gave its inhabitants a renewed confidence in themselves, which remains very present in the bid made for Universal Expo 2015.

Despite its advantageous location and its heritage, until recently İzmir has suffered, as one author puts it, from a "sketchy understanding" in the eyes of outsiders. When the Ottomans took over İzmir in the 15th century they did not inherit compelling historical memories, unlike the two other keys of the trade network, namely İstanbul and Aleppo. Its emergence as a major international port as of the 17th century was largely a result of the attraction it exercised over foreigners, and the city's european orientation. [2] Very different people found İzmir attractive over the ages and the city has always been governed by fresh inspirations, including for the very location of its center, and is quick to adopt novelties and projects. Nevertheless, its successful completion of the 2005 Universiade games gave its inhabitants a renewed confidence in themselves, which remains very present in the bid made for Universal Expo 2015.

Names and etymology

Names and etymologyUndisturbed wild horses roam in Mount Yamanlar overlooking İzmir and the neighboring Mount Sipylus (Mount Spil) National Park.

The name of a locality called Ti-smurna is mentioned in some of the Level II tablets from the Assyrian colony in Kültepe (first half of the 2nd millennium B.C.), with the prefix ti- identifying a proper name, although it is not established with certainty that this name refers to İzmir.[3] Some would see in the city's name a reference to the name of an Amazon called Smirna.

The region of İzmir was situated on the southern fringes of the "Yortan culture" in Anatolia's prehistory, the knowledge of which is almost entirely drawn from its cemeteries [4], and in the second half of the 2nd millennium B.C., in the western end of the extension of the yet largely obscure Arzawa Kingdom, an offshoot and usually a dependency of the Hittites, who themselves spread their direct rule as far as the coast during their Great Kingdom. That the realm of the local Luwian ruler who legated the 13th century B.C. Kemalpaşa Karabel rock carving at a distance of only 50 km from İzmir was called Mira may also leave ground for association with the city's name. [5]

The oldest rendering in Greek of the city's name we know is the Aeolic Greek Μύρρα Mýrrha, corresponding to the later Ionian and Attic Σμύρνα (Smýrna) or Σμύρνη (Smýrnē), both presumably descendants of a Proto-Greek form *Smúrnā. It would be linked to the name of the Myrrha commifera shrub, a plant that produces the aromatic resin called myrrh and is indigenous to the Middle East and northeastern Africa. The Romans took this name over as Smyrna which is the name still used in English when referring to the city in pre-Turkish periods. The name İzmir (Ottoman Turkish: إزمير İzmir) is the modern Turkish version of the same name.

In Greek it is Σμύρνη (Smýrni), Իզմիր (Izmir) in Armenian, Smirne in Italian, and Izmir (without the Turkish dotted İ) in Ladino.

In English, the city was called Smyrna until the early twentieth century and has been called İzmir since. In written Turkish it is spelled with a dotted İ at the beginning.

İzmir is nicknamed "Occidental İzmir" or "The Pearl of the Aegean".

History

Ancient age

The city is one of the oldest settlements of the Mediterranean basin. The 2004 discovery of Yeşilova Höyük and the neighboring höyük of Yassıtepe, situated in the plain of Bornova, reset the starting date of the city's past further back than was previously thought. The findings of the two seasons of excavations carried out in Yeşilova Höyük by a team of archaeologists from İzmir's Ege University under the direction of Associate Professor Zafer Derin indicate three levels, two of which are prehistoric. Level 2 bears traces of early to mid-Chalcolithic, and the Level 3 of Neolithic settlements. These two levels would have been inhabited by the indigenous peoples of İzmir, very roughly, between 6500 to 4000 BC. With the seashore drawing away in time, the site was later used as a cemetery (several graves containing artifacts dating, roughly, from 3000 BC were found).

By 1500 BC the region fell under the influence of the Central Anatolian Hittite Empire. The Hittites possessed a script and several localities near İzmir were mentioned in their records. They are associated with the vestiges on top of the Mount Yamanlar overlooking the gulf from the northeast.

In connection with the silt brought by the streams that join the sea along the coastline of the gulf's end, the settlement that later formed the core of Old Smyrna was founded more to the north-west of the prehistoric settlement and on the slopes of the Mount Yamanlar, on a hill in the present-day quarter of Bayraklı where settlement is thought to stretch back as far as the 3rd millennium BC. The hill was possibly an island at the time or perhaps connected to the mainland by a very narrow isthmus. This İzmir preceding Old Smyrna was one of the most advanced cultures in Anatolia of its time and on a par with Troy. This phase of the city's history is also when it was associated with the Amazon Smirna. The presence of a vineyard of İzmir's Wine and Beer Factory on this hill, also called Tepekule, prevented the urbanization of the site and facilitated the excavations that started in the 1960s by Ekrem Akurgal.

However, in the 1200s BC, invasions from the Balkans destroyed Troy VII and Hattusas, the capital of the Hittite capital. Central and Western Anatolia fell back into a Dark Age that lasted until the emergence of the Phrygian civilization in the 8th century BC.

In connection with the silt brought by the streams that join the sea along the coastline of the gulf's end, the settlement that later formed the core of Old Smyrna was founded more to the north-west of the prehistoric settlement and on the slopes of the Mount Yamanlar, on a hill in the present-day quarter of Bayraklı where settlement is thought to stretch back as far as the 3rd millennium BC. The hill was possibly an island at the time or perhaps connected to the mainland by a very narrow isthmus. This İzmir preceding Old Smyrna was one of the most advanced cultures in Anatolia of its time and on a par with Troy. This phase of the city's history is also when it was associated with the Amazon Smirna. The presence of a vineyard of İzmir's Wine and Beer Factory on this hill, also called Tepekule, prevented the urbanization of the site and facilitated the excavations that started in the 1960s by Ekrem Akurgal.

However, in the 1200s BC, invasions from the Balkans destroyed Troy VII and Hattusas, the capital of the Hittite capital. Central and Western Anatolia fell back into a Dark Age that lasted until the emergence of the Phrygian civilization in the 8th century BC.

Iron Age houses were small, one-room buildings. The oldest house unearthed in Bayraklı is dated to 925 and 900 BC. The walls of this well-preserved one-roomed house (2.45 x 4 m) were made of sun-dried bricks and the roof of the house was made of reeds. Around that time, people started to protect the city with thick ramparts made of sun-dried bricks. From then on Smyrna achieved an identity of city-state. About 1,000 lived inside the city walls, with others living in near-by villages, where fields, olive trees, vineyards, and the workshops of potters and stonecutters were located. People generally made their living through agriculture and fishing.

HomerHomer, referred to as Melesigenes which means "Child of Meles Brook" is said to have been born in Smyrna. Meles Brook is located within the city of İzmir and still carries the same name. Aristotle recounts: "Kriteis... gives birth to Homer near Meles Brook and dies after. Maion brings this child up and names him as Melesigenes ("Child of Meles") to emphasize the place where he was born." Six other cities claimed Homer as their countryman [8], but the main belief is that Homer was born in Ionia and combined with written evidence, it is generally admitted that Smyrna and Chios put forth the strongest arguments in claiming Homer.

HomerHomer, referred to as Melesigenes which means "Child of Meles Brook" is said to have been born in Smyrna. Meles Brook is located within the city of İzmir and still carries the same name. Aristotle recounts: "Kriteis... gives birth to Homer near Meles Brook and dies after. Maion brings this child up and names him as Melesigenes ("Child of Meles") to emphasize the place where he was born." Six other cities claimed Homer as their countryman [8], but the main belief is that Homer was born in Ionia and combined with written evidence, it is generally admitted that Smyrna and Chios put forth the strongest arguments in claiming Homer.

From the 8th century BC

Old SmyrnaThe term Old Smyrna is used to describe the Greek city-state of the classical era located at the urban settlement in Tepekule, Bayraklı, to make a distinction with Smyrna re-built later on the slopes of Mt. Pagos (Kadifekale today). The most important sanctuary of Old Smyrna was the Temple of Athena, restored somewhat today. The most ancient ruins preserved to our day date back to 725-700 BC.

Greek settlement in Old Smyrna is attested by the presence of pottery dating from about 1000 BC onwards. The city was settled at first by the Aeolians, but shortly thereafter seized by the Ionians and Smyrna was added to the twelve Ionian cities. As such, the city set out on its way to become one of the most prominent cultural and commercial centers of that period in the Mediterranean basin. [9]

The period in which Old Smyrna reached its peak was between 650-545 BC. This period was considered to be the most powerful period of the whole Ionian civilization. Under the leadership of the city of Miletus, Ionian colonies were established in Egypt, Syria, the west coasts of Lebanon, the Marmara region, around the Black Sea and in eastern Greece. The colonies competed amongst themselves, and were a match for Greece proper in many areas. Smyrna by this point was no longer a small town, but an urban center that took part in the Mediterranean trade.

One of the most important signs of that period is the widespread use of writing beginning with 650 BC. There are many inscriptions on presentations of the gifts dedicated to the goddess Athena, whose temple dates to 640-580 BC.

The oldest model of a many-roomed-type house of this period was found in ancient Smyrna. Known to be the oldest house having so many rooms under its roof, this house was built in the second half of 7th century BC. The house has two floors and has five rooms with a courtyard. The houses before this type were composed of megarons standing adjacent to each other. Smyrna was built on the Hippodamian system in which streets run north-south and east-west and intersect at right angles. The houses all faced to the south.

This city plan, which took the name Hippodamus later in the 5th century BC, followed a pattern familiar in the Near East. The city plan in the Bayraklı Höyük (mound) is the earliest example of this type in the Western Hemisphere. The most ancient paved streets of the Ionian civilization have been discovered in ancient Smyrna.

The riches of the city impressed the Lydians and attracted them to Smyrna. The Lydian army conquered the city in about 610-600 BC and burned and destroyed parts of the city. Soon afterwards, another invasion, this time Persian, effectively ended Old Smyrna's history as an urban center of note. The Persian Emperor, determined to punish the cities that refused to give him support in his campaign against the Lydians, attacked the coastal cities of the Aegean after having conquered Sardis, the capital of Lydia. As a result, old Smyrna was destroyed in 545 BC.

Alexander the GreatAlexander the Great re-founded the city in about 300 BC. Alexander had defeated the Persians in several battles and finally the emperor Darius himself at Issus in 333 BC. The cities of the region witnessed a great resurgence in their population. During this period, Rhodes and Pergamon reached populations of over 100,000. Ephesus, Antioch and Alexandria reached a population of over 400,000. Old Smyrna, which had been founded on a small hill, was only sufficient for a few thousand people, so the new and larger city had been founded on the slopes of Mount Pagos (Kadifekale) in 300 BC. The flat-topped hill seemed destined by nature to be the acropolis of an ancient city.

RomansHaving become a Roman territory in 133 BC, Smyrna enjoyed a golden period for the second time. Due to the importance that the city achieved, the Roman emperors who came to Anatolia also visited Smyrna. Emperor Hadrian also visited Smyrna in his journey from 121 to 125. He ordered the construction of a silo near the docks.

In 178 AD the city was devastated by an earthquake. Considered to be one of the most severe disasters that the city has faced in its history, the earthquake razed the town to the ground. The destruction was so great that the support of the Empire for rebuilding was necessary. Emperor Marcus Aurelius contributed greatly to the rebuilding activities and the city was re-founded again. The state agora as restored during this period.

Various works of architecture are thought to have been built in the city during the Roman Empire period. The streets were completely paved with stones, and paved streets became preponderant in the city.

After the Roman Empire's division into two distinct entities, Smyrna became a territory of the Eastern Roman Empire. It preserved its status as a notable religious center in the early times of the Byzantine Empire. However, the city did decrease in size greatly during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Age, never returning to the Roman levels of prosperity.

The period in which Old Smyrna reached its peak was between 650-545 BC. This period was considered to be the most powerful period of the whole Ionian civilization. Under the leadership of the city of Miletus, Ionian colonies were established in Egypt, Syria, the west coasts of Lebanon, the Marmara region, around the Black Sea and in eastern Greece. The colonies competed amongst themselves, and were a match for Greece proper in many areas. Smyrna by this point was no longer a small town, but an urban center that took part in the Mediterranean trade.

One of the most important signs of that period is the widespread use of writing beginning with 650 BC. There are many inscriptions on presentations of the gifts dedicated to the goddess Athena, whose temple dates to 640-580 BC.

The oldest model of a many-roomed-type house of this period was found in ancient Smyrna. Known to be the oldest house having so many rooms under its roof, this house was built in the second half of 7th century BC. The house has two floors and has five rooms with a courtyard. The houses before this type were composed of megarons standing adjacent to each other. Smyrna was built on the Hippodamian system in which streets run north-south and east-west and intersect at right angles. The houses all faced to the south.

This city plan, which took the name Hippodamus later in the 5th century BC, followed a pattern familiar in the Near East. The city plan in the Bayraklı Höyük (mound) is the earliest example of this type in the Western Hemisphere. The most ancient paved streets of the Ionian civilization have been discovered in ancient Smyrna.

The riches of the city impressed the Lydians and attracted them to Smyrna. The Lydian army conquered the city in about 610-600 BC and burned and destroyed parts of the city. Soon afterwards, another invasion, this time Persian, effectively ended Old Smyrna's history as an urban center of note. The Persian Emperor, determined to punish the cities that refused to give him support in his campaign against the Lydians, attacked the coastal cities of the Aegean after having conquered Sardis, the capital of Lydia. As a result, old Smyrna was destroyed in 545 BC.

Alexander the GreatAlexander the Great re-founded the city in about 300 BC. Alexander had defeated the Persians in several battles and finally the emperor Darius himself at Issus in 333 BC. The cities of the region witnessed a great resurgence in their population. During this period, Rhodes and Pergamon reached populations of over 100,000. Ephesus, Antioch and Alexandria reached a population of over 400,000. Old Smyrna, which had been founded on a small hill, was only sufficient for a few thousand people, so the new and larger city had been founded on the slopes of Mount Pagos (Kadifekale) in 300 BC. The flat-topped hill seemed destined by nature to be the acropolis of an ancient city.

RomansHaving become a Roman territory in 133 BC, Smyrna enjoyed a golden period for the second time. Due to the importance that the city achieved, the Roman emperors who came to Anatolia also visited Smyrna. Emperor Hadrian also visited Smyrna in his journey from 121 to 125. He ordered the construction of a silo near the docks.

In 178 AD the city was devastated by an earthquake. Considered to be one of the most severe disasters that the city has faced in its history, the earthquake razed the town to the ground. The destruction was so great that the support of the Empire for rebuilding was necessary. Emperor Marcus Aurelius contributed greatly to the rebuilding activities and the city was re-founded again. The state agora as restored during this period.

Various works of architecture are thought to have been built in the city during the Roman Empire period. The streets were completely paved with stones, and paved streets became preponderant in the city.

After the Roman Empire's division into two distinct entities, Smyrna became a territory of the Eastern Roman Empire. It preserved its status as a notable religious center in the early times of the Byzantine Empire. However, the city did decrease in size greatly during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Age, never returning to the Roman levels of prosperity.

Smyrna becomes İzmir

Çaka Bey and the Seljuk TurksTurks first captured Smyrna under the Seljuk commander Çaka Bey in 1076, along with Klazomenai, Foça and a number of Aegean Islands. Çaka Bey used İzmir as a base for naval raids. After his death in 1102, the city and the neighboring region was recaptured by the Byzantine Empire. Smyrna was then captured by the Knights of Rhodes when Constantinople was conquered by the Crusaders in 1204, but the Nicaean Empire could reclaim possession of the city soon afterwards, albeit by according vast concessions to Genoese allies who kept one of the city's castles.

The sons of AydınSmyrna was recaptured by the Turks in early 14th century when, Umur Bey, the son of the founder of the Beylik of Aydın captured first the upper fort of Kadifekale, and then the lower port castle of Ok Kalesi. As Çaka Bey had done two centuries before, Umur Bey used the city as a base for naval raids. In 1344, taking advantage of a distracted Aydınoğlu, the Genoese took back the lower castle. A sixty-year period of uneasy cohabitation between the two powers followed Umur Bey's death.

TamerlaneSmyrna was captured by the Ottomans for the first time in 1389 by Bayezid I, who led his armies toward the five Western Anatolian Turkish Beyliks in the winter of the same year he had ascended the throne. The Ottoman take-over took place virtually without conflict. However, in 1402, Tamerlane won the Battle of Ankara against the Ottomans and put a serious check on the fortunes of the Ottoman state for the two following decades. Tamerlane gave back the territories of most of the Anatolian Turkish Beyliks to their former ruling dynasties, and he came in person to İzmir to lodge the only battle of his career against a non-Muslim power, finally taking back the port castle from the Genoese.

The sons of AydınSmyrna was recaptured by the Turks in early 14th century when, Umur Bey, the son of the founder of the Beylik of Aydın captured first the upper fort of Kadifekale, and then the lower port castle of Ok Kalesi. As Çaka Bey had done two centuries before, Umur Bey used the city as a base for naval raids. In 1344, taking advantage of a distracted Aydınoğlu, the Genoese took back the lower castle. A sixty-year period of uneasy cohabitation between the two powers followed Umur Bey's death.

TamerlaneSmyrna was captured by the Ottomans for the first time in 1389 by Bayezid I, who led his armies toward the five Western Anatolian Turkish Beyliks in the winter of the same year he had ascended the throne. The Ottoman take-over took place virtually without conflict. However, in 1402, Tamerlane won the Battle of Ankara against the Ottomans and put a serious check on the fortunes of the Ottoman state for the two following decades. Tamerlane gave back the territories of most of the Anatolian Turkish Beyliks to their former ruling dynasties, and he came in person to İzmir to lodge the only battle of his career against a non-Muslim power, finally taking back the port castle from the Genoese.

The Ottomans

In 1425, Murad II re-captured İzmir for the Ottomans for the second time and from the last bey of Aydın, İzmiroğlu Cüneyd Bey. During the campaign, the Ottomans were assisted by the forces of the Knights Hospitaller who pressed the Sultan for possession of the port castle. The sultan refused despite the resulting tensions between the two camps, and he gave the Templars the permission to build a castle in Petronium (Bodrum Castle) instead.

The city became a typical Ottoman sanjak (sub-province) inside the larger Ottoman eyalet (province) of Aydın. Two notable events for the city during the rest of the 15th century were a Venetian raid in 1475 and the arrival of Jews from Spain after 1492, who later made İzmir one of their principal centers in Ottoman lands.

The Ottomans also allowed İzmir's inner bay dominated by the port castle to silt up progressively (the location of present-day Kemeraltı bazaar zone) and the port castle ceased to be of use.

International port city

In 1425, Murad II re-captured İzmir for the Ottomans for the second time and from the last bey of Aydın, İzmiroğlu Cüneyd Bey. During the campaign, the Ottomans were assisted by the forces of the Knights Hospitaller who pressed the Sultan for possession of the port castle. The sultan refused despite the resulting tensions between the two camps, and he gave the Templars the permission to build a castle in Petronium (Bodrum Castle) instead.

The city became a typical Ottoman sanjak (sub-province) inside the larger Ottoman eyalet (province) of Aydın. Two notable events for the city during the rest of the 15th century were a Venetian raid in 1475 and the arrival of Jews from Spain after 1492, who later made İzmir one of their principal centers in Ottoman lands.

The Ottomans also allowed İzmir's inner bay dominated by the port castle to silt up progressively (the location of present-day Kemeraltı bazaar zone) and the port castle ceased to be of use.

International port city

With the privileged trading conditions accorded to foreigners in 1620 (the infamous capitulations that were later to cause a serious threat and setback for the Ottoman state in its decline), İzmir set out on its way to become one of the foremost trade centers of the Empire. Foreign consulates moved in from Sakız (Chios) and were in the city (1619 for the French Consulate, 1621 for the British), serving as trade centers for their nations. Each consulate had its own quay and the ships under their flag would anchor there. The long campaign for the conquest of Crete (22 years between 1648-1669) also considerably enhanced İzmir's position within the Ottoman realm since the city served as port of dispatch and supply for the troops.

The city faced a 1676 plague, an earthquake in 1688 and a great fire in 1743, but continued to grow. In 1866 the British-built 130 km (81 mi) railway line to Aydın was opened (the first Ottoman Empire line). By that time, İzmir had a considerable segment of its population composed of French, English, Dutch and Italian merchants, adding to numerous immigrants coming from other parts of the Ottoman Empire. In fact, a class of intermediaries, composed of Greeks and, some time later and to a lesser extent, by Armenians, as well as some among the generally poorer Jews, started to take hold. The attraction the city exercised for merchants and middlemen gradually changed the demographic structure of the city, its culture and its Ottoman character.

The city faced a 1676 plague, an earthquake in 1688 and a great fire in 1743, but continued to grow. In 1866 the British-built 130 km (81 mi) railway line to Aydın was opened (the first Ottoman Empire line). By that time, İzmir had a considerable segment of its population composed of French, English, Dutch and Italian merchants, adding to numerous immigrants coming from other parts of the Ottoman Empire. In fact, a class of intermediaries, composed of Greeks and, some time later and to a lesser extent, by Armenians, as well as some among the generally poorer Jews, started to take hold. The attraction the city exercised for merchants and middlemen gradually changed the demographic structure of the city, its culture and its Ottoman character.

In the late 19th century, the port was threatened by a build-up of silt in the gulf and an initiative was undertaken to move the Gediz River bed to its present-day northern course, instead of letting it flow into the gulf, in order to redirect the silt.

Following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, the victors had, for a time, intended to carve up large parts of Anatolia under respective zones of influence and offered the western regions of Turkey to Greece with the Treaty of Sèvres. On 15 May 1919 the Greek Army occupied İzmir, but the Greek expedition towards central Anatolia turned into a disaster for both that country and for the local Greeks of Turkey.

The Turkish Army retook possession of İzmir on 9 September 1922, effectively ending the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) in the field. Part of the Greek population of the city was forced to seek refuge in the nearby Greek islands together with the departing Greek troops, while the rest left in the frame of the ensuing 1923 agreement for the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations, which was a part of the

Following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, the victors had, for a time, intended to carve up large parts of Anatolia under respective zones of influence and offered the western regions of Turkey to Greece with the Treaty of Sèvres. On 15 May 1919 the Greek Army occupied İzmir, but the Greek expedition towards central Anatolia turned into a disaster for both that country and for the local Greeks of Turkey.

The Turkish Army retook possession of İzmir on 9 September 1922, effectively ending the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) in the field. Part of the Greek population of the city was forced to seek refuge in the nearby Greek islands together with the departing Greek troops, while the rest left in the frame of the ensuing 1923 agreement for the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations, which was a part of the

Lausanne Treaty.

The war, and especially its events specific to İzmir, like the fire that broke out on 13 September 1922, one of the greatest disasters İzmir ever experienced, influence the psyches of the two nations to this day. For the Turks, the occupation was marked from its very first day by the "first bullet" fired on Greek detachments by the journalist Hasan Tahsin and the killing by bayonet coups of Colonel Fethi Bey and his unarmed soldiers in the historic casern of the city (Sarı Kışla — the Yellow Casern), for refusing to shout "Zito o Venizelos" (Long Live Venizelos). The Turkish side, on the other hand, was accused of a number of atrocities against the Greek and Armenian communities in İzmir, including the lynching of the Orthodox Metropolitan Chrysostomos following their recapture of the city on 9 September 1922. A Turkish source on İzmir's oral history also confirms that in 1922, "hat-wearers were thrown into the sea, just like, back in 1919, fez-wearers were thrown" [10]. The lack of comprehensive and reliable sources from the period, combined with nationalist feelings running high on both sides, and mutual distrust between the conflicting parties, has led to each side accusing each other for decades of committing atrocities during the period.

The city was, once again, gradually rebuilt after the proclamation of the Turkish Republic in 1923.

The war, and especially its events specific to İzmir, like the fire that broke out on 13 September 1922, one of the greatest disasters İzmir ever experienced, influence the psyches of the two nations to this day. For the Turks, the occupation was marked from its very first day by the "first bullet" fired on Greek detachments by the journalist Hasan Tahsin and the killing by bayonet coups of Colonel Fethi Bey and his unarmed soldiers in the historic casern of the city (Sarı Kışla — the Yellow Casern), for refusing to shout "Zito o Venizelos" (Long Live Venizelos). The Turkish side, on the other hand, was accused of a number of atrocities against the Greek and Armenian communities in İzmir, including the lynching of the Orthodox Metropolitan Chrysostomos following their recapture of the city on 9 September 1922. A Turkish source on İzmir's oral history also confirms that in 1922, "hat-wearers were thrown into the sea, just like, back in 1919, fez-wearers were thrown" [10]. The lack of comprehensive and reliable sources from the period, combined with nationalist feelings running high on both sides, and mutual distrust between the conflicting parties, has led to each side accusing each other for decades of committing atrocities during the period.

The city was, once again, gradually rebuilt after the proclamation of the Turkish Republic in 1923.

Population

The period after the 1960's and the 1970's saw another blow to İzmir's tissue - as serious as the 1922 fire for many inhabitants - when local administrations tended to neglect İzmir's traditional values and landmarks. Some administrators were not always in tune with the central government in Ankara and regularly fell short of subsidies, and the city absorbed huge immigration waves from Anatolian inland causing a population explosion. Today it is not surprising to see many inhabitants of İzmir (in line with natives of such other prominent Turkish cities as Istanbul, Bursa, Adana and Mersin) look back to a cozier and more manageable city, which came to an end in the last few decades, with nostalgia. The Floor Ownership Law of 1965 (Kat Mülkiyeti Kanunu), allowing and encouraging arrangements between house or land proprietors and building contractors in which each would share the benefits in rent of 8-floor apartment blocks built in the place of the former single house, proved especially disastrous for the urban landscape.

İzmir is also home to Turkey's second largest Jewish community after Istanbul, still 2,500 strong.[11] The community is still concentrated in their traditional quarter of Karataş. The most famous figures the Jewish community of İzmir has produced are Sabbatai Zevi and Darío Moreno.

The Levantines of İzmir, who are mostly of Genoese and to a lesser degree of French and Venetian descent, live mainly in the districts of Bornova and Buca. One of the most prominent present-day figures of the community is Caroline Giraud Koç, wife of industrialist Mustafa Koç. Koç Holding is one of the largest family-owned industrial conglomerates in the world.

İzmir is also home to Turkey's second largest Jewish community after Istanbul, still 2,500 strong.[11] The community is still concentrated in their traditional quarter of Karataş. The most famous figures the Jewish community of İzmir has produced are Sabbatai Zevi and Darío Moreno.

The Levantines of İzmir, who are mostly of Genoese and to a lesser degree of French and Venetian descent, live mainly in the districts of Bornova and Buca. One of the most prominent present-day figures of the community is Caroline Giraud Koç, wife of industrialist Mustafa Koç. Koç Holding is one of the largest family-owned industrial conglomerates in the world.

Main sights

Standing on Mount Yamanlar (Dağı), the tomb of Tantalus is an example of the tholos type monumental tombs. The grave room of Tantalus' tumulus was in the plan of the fountain, displaying a style called isopata, meaning the construction has a rectangle plan, covered by vaults made with a corbel technique. This monumental work is thought to be the tomb of the Basileus or Tyrant who ruled ancient Smyrna in 580-520 BC.

One of the more pronounced elements of Izmir harbor is the Clock Tower, a beautiful marble tower that rests in the middle of the Konak district, standing 25 meters in height. It was designed by the Levantine French architect Raymond Charles Père in 1901 for the commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the ascension of Abdülhamid II. The clock workings themselves were given as a gift to the then Ottoman Empire by Kaiser Wilhelm II. The tower features four fountains which are placed around the base in a circular pattern, and the columns are inspired by North African themes.

The Agora of Smyrna is well preserved, and is arranged into the Agora Open Air Museum of İzmir, although important parts buried under modern buildings, waiting to be brought to daylight. Serious consideration is also being given to uncovering the ancient theatre of Smyrna where St. Polycarp was martyred, buried under an urban zone on the slopes of Kadifekale. It was distinguishable until the 19th century, as evident by the sketchings done at the time. On top of the same hill soars an ancient castle which is one of the landmarks of İzmir.

The Kemeraltı bazaar zone set up by the Ottomans, combined with the Agora, rests near the slopes of Kadifekale. İzmir has had three castles historically- Kadifekale (Pagos), the portuary Ok Kalesi (Neon Kastron, St. Peter), and Sancakkale, which remained vital to İzmir's security for centuries. Sancakkale is situated in the present-day İnciraltı quarter between Balçova and Narlıdere districts, on the southern shore of the Gulf of İzmir. It is at a key point where the strait allows entry into the innermost tip of the Gulf at its narrowest, and due to shallow waters through a large part of this strait, ships have sailed close to the castle. [12]

There are nine synagogues in İzmir, concentrated either in the traditional Jewish quarter of Karataş or in Havra Sokak (Synagogue street) in Kemeraltı, and they all bear the signature of the 19th century when they were built or re-constructed in depth on the basis of former buildings.

The İzmir Birds Paradise in Çiğli, a bird sanctuary near Karşıyaka, contains 205 species of birds. There are 63 species of domestic birds, 54 species of summer migratory birds, 43 species of winter migratory birds, 30 species of transit birds. 56 species of birds have been breeding in the Park. İzmir Bird's Paradise which covers 80 square kilometres was registered as "The protected area for water birds and for their breeding" by Ministry of Forestry in 1982.

The Agora of Smyrna is well preserved, and is arranged into the Agora Open Air Museum of İzmir, although important parts buried under modern buildings, waiting to be brought to daylight. Serious consideration is also being given to uncovering the ancient theatre of Smyrna where St. Polycarp was martyred, buried under an urban zone on the slopes of Kadifekale. It was distinguishable until the 19th century, as evident by the sketchings done at the time. On top of the same hill soars an ancient castle which is one of the landmarks of İzmir.

The Kemeraltı bazaar zone set up by the Ottomans, combined with the Agora, rests near the slopes of Kadifekale. İzmir has had three castles historically- Kadifekale (Pagos), the portuary Ok Kalesi (Neon Kastron, St. Peter), and Sancakkale, which remained vital to İzmir's security for centuries. Sancakkale is situated in the present-day İnciraltı quarter between Balçova and Narlıdere districts, on the southern shore of the Gulf of İzmir. It is at a key point where the strait allows entry into the innermost tip of the Gulf at its narrowest, and due to shallow waters through a large part of this strait, ships have sailed close to the castle. [12]

There are nine synagogues in İzmir, concentrated either in the traditional Jewish quarter of Karataş or in Havra Sokak (Synagogue street) in Kemeraltı, and they all bear the signature of the 19th century when they were built or re-constructed in depth on the basis of former buildings.

The İzmir Birds Paradise in Çiğli, a bird sanctuary near Karşıyaka, contains 205 species of birds. There are 63 species of domestic birds, 54 species of summer migratory birds, 43 species of winter migratory birds, 30 species of transit birds. 56 species of birds have been breeding in the Park. İzmir Bird's Paradise which covers 80 square kilometres was registered as "The protected area for water birds and for their breeding" by Ministry of Forestry in 1982.

Cuisine of İzmir

İzmir's cuisine has largely been affected by its multicultural history, hence the large variety of food originating from the Aegean, Mediterranean and Anatolian regions. Another factor is the large area of land surrounding the region which grows a rich selection of vegetables. Some of the common dishes found here are tarhana soup (made from dried yoghurt and tomatoes), İzmir köfte, keşkek (boiled wheat with meat), zerde (sweetened rice with saffron) and mücver (made from zucchini and eggs).

Historically, as a result of the influx of Greek refugees from İzmir (as well as from other parts of Asia Minor and Istanbul) to mainland Greece after 1922, the cuisine of İzmir has had an enormous impact on Greek cuisine, exporting many sophisticated spices and foods.

Historically, as a result of the influx of Greek refugees from İzmir (as well as from other parts of Asia Minor and Istanbul) to mainland Greece after 1922, the cuisine of İzmir has had an enormous impact on Greek cuisine, exporting many sophisticated spices and foods.

Festivals

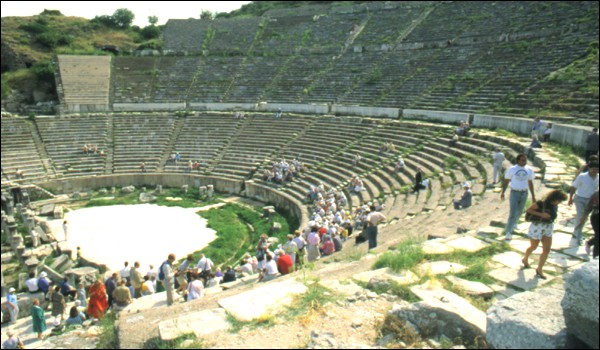

The İzmir International Festival beginning in mid-June and continuing to mid-July, has been organized since 1987. During the annual festival, many world-class performers such as soloists and virtuosi, orchestras, dance companies, rock and jazz groups including Ray Charles, Paco de Lucia, Joan Baez, Martha Graham Dance Company, Tanita Tikaram, Jethro Tull, Leningrad Philarmonic Orchestra, Chris De Burgh, Sting, Moscow State Philarmony Orchestra, Jan Garbarek, Red Army Chorus, Academy of St. Martin in the Field, Kodo, Chick Corea and Origin, New York City Ballet, Nigel Kennedy, Bryan Adams, James Brown, Elton John, Kiri Te Kanawa, Mikhail Barishnikov and Josep Carreras have given recitals and performances at various venues in the city and surrounding areas, including the ancient theatres at Ephesus and Metropolis (an antique Ionian city situated near the town of Torbalı). This festival is the member of "European Festivals Association" since 2003.

The İzmir European Jazz Festival is among the numerous events organized every year by İKSEV (The İzmir Foundation for Culture, Arts and Education) since 1994. The festival aims to bring together masters and lovers of jazz in the attempt to generate feelings of love, friendship and peace.

International İzmir Short Film Festival is organized since 1999 and the member of European Coordination of Film Festivals.

İzmir Metropolitan Municipality is building Ahmet Adnan Saygun Culture and Art Center in Güzelyalı over an area of 21.000 m2 in order to contribute to the city's culture and art life. The acoustics of the center has been prepared by ARUP which is a world famous company in its own field . The center will serve from summer of 2008.

The İzmir European Jazz Festival is among the numerous events organized every year by İKSEV (The İzmir Foundation for Culture, Arts and Education) since 1994. The festival aims to bring together masters and lovers of jazz in the attempt to generate feelings of love, friendship and peace.

International İzmir Short Film Festival is organized since 1999 and the member of European Coordination of Film Festivals.

İzmir Metropolitan Municipality is building Ahmet Adnan Saygun Culture and Art Center in Güzelyalı over an area of 21.000 m2 in order to contribute to the city's culture and art life. The acoustics of the center has been prepared by ARUP which is a world famous company in its own field . The center will serve from summer of 2008.

Transportation

Connection with other cities and countries

Air: The city has an airport (Adnan Menderes Airport) well served with connections to Turkish and international destinations. Its new international terminal was opened in September 2006 and the airport is set on its way for becoming one of the busiest in Turkey. The city-airport shuttles are assured by buses operated by a private company (web page for İzmir) and along stops that follow two lines only, the first connecting Karşıyaka in the city's northern part to the airport and the second between Alsancak in the south and the airport. Trains remain a comparatively slow alternative, the subway that will reach the airport is under construction, while the taxis are not cheap and can cost up to fifty U.S. dollars depending on the distance.

Bus: A recently-built large bus terminal (Otogar) in Altındağ suburb on the outkirts of the city has intercity buses to points all over Turkey. It is quite easy to reach the bus terminal since bus companies' shuttle services to the terminal pick up customers from each of their branch offices scattered across the city at regular intervals. These shuttles are a free service encountered everywhere in Turkey.

Rail: The city has rail service from historic terminals in downtown (such as the famous Alsancak Terminal (1858) which is the oldest train station in Turkey) to Ankara in the east and Aydın in the south. An express train to Bandırma, to reach the Sea of Marmara port city in four hours and to combine the journey with İDO's HSC services from Bandırma to İstanbul is in service since February 2007.

Bus: A recently-built large bus terminal (Otogar) in Altındağ suburb on the outkirts of the city has intercity buses to points all over Turkey. It is quite easy to reach the bus terminal since bus companies' shuttle services to the terminal pick up customers from each of their branch offices scattered across the city at regular intervals. These shuttles are a free service encountered everywhere in Turkey.

Rail: The city has rail service from historic terminals in downtown (such as the famous Alsancak Terminal (1858) which is the oldest train station in Turkey) to Ankara in the east and Aydın in the south. An express train to Bandırma, to reach the Sea of Marmara port city in four hours and to combine the journey with İDO's HSC services from Bandırma to İstanbul is in service since February 2007.

Transportation within the city

Urban ferries: Taken over by İzmir Metropolitan Municipality since 2000 and operated within the structure of a private company (İzdeniz), İzmir's urban ferry services for passengers and vehicles are very much a part of the life of the inhabitants of this city located along the deep end of a large gulf. 24 ferries shuttle between 8 quays (clockwise Bostanlı, Karşıyaka, Bayraklı, Alsancak, İzmir, Pasaport, İzmir, Konak, Göztepe and Üçkuyular). Special lines to points further out in the gulf are also put in service during summer, transporting excursion or holiday makers. These services are surprisingly cheap and it is not unusual to see natives or visitors taking a ferry ride simply as a pastime.

Metro: İzmir has a subway network (rapid transit over the surface in parts) that is constantly being extended with new stations being put in service. The network "İzmir Metrosu", consisting of one line, starts from Üçyol station in Hatay in the southern portion of the metropolitan area and runs towards northeast to end in Bornova. The line is 11.6 km (7.2 mi) long.

Metro: İzmir has a subway network (rapid transit over the surface in parts) that is constantly being extended with new stations being put in service. The network "İzmir Metrosu", consisting of one line, starts from Üçyol station in Hatay in the southern portion of the metropolitan area and runs towards northeast to end in Bornova. The line is 11.6 km (7.2 mi) long.

The stations are: 1) Üçyol, 2) Konak, 3) Çankaya, 4) Basmane, 5) Hilal, 6) Halkapınar, 7) Stadyum, 8) Sanayi, 9) Bölge, 10) Bornova. An extension of the line between Üçyol and Üçkuyular, which aims to serve the southern portion of the city more efficiently, is currently under construction.

Basic fare on the Metro is TRL 1.25 but only TRL 0.95 if the Kentkart is used. About 12% of passengers pay cash and the rest use Kentkart, 35% at reduced rate and 53% at standard rate. The Metro carries about 30 million passengers/year and to the end of September 2005 160 million passengers had travelled since the opening in May 2000.

A more ambitious venture that begun involves the construction of a new 80 km (50 mi) line between Aliağa district in the north, where a oil refinery and its port are located, to Menderes district in the south, to reach and serve Adnan Menderes Airport. This new line will have a connection to the existing line and it is planned to be finished in 2008 autumn. It will comprise 32 stations and the full ride between the two ends of the line will only take 86 minutes.

Bus: All major districts are covered by a dense municipal bus network under the name ESHOT. The name is derived from the E elektrik; S su (water); H havgazi (gas); O otobus (bus) and T trolybus. Electricity, water and gas are now supplied by separate undertakings and the trolleybuses ceased in 1992. The bus company has inherited the original name. ESHOT operates about 1,500 buses with a staff of 2,700. It has five garages at Karatas, Gumruk, Basmahane, Yesilyurt and Konak. A privately owned company, Izulas, operates 400 buses from two garages, running services under contract for ESHOT. These scheduled services are supplemented by privately-owned minibus or dolmuş services.

Basic fare on the Metro is TRL 1.25 but only TRL 0.95 if the Kentkart is used. About 12% of passengers pay cash and the rest use Kentkart, 35% at reduced rate and 53% at standard rate. The Metro carries about 30 million passengers/year and to the end of September 2005 160 million passengers had travelled since the opening in May 2000.

A more ambitious venture that begun involves the construction of a new 80 km (50 mi) line between Aliağa district in the north, where a oil refinery and its port are located, to Menderes district in the south, to reach and serve Adnan Menderes Airport. This new line will have a connection to the existing line and it is planned to be finished in 2008 autumn. It will comprise 32 stations and the full ride between the two ends of the line will only take 86 minutes.

Bus: All major districts are covered by a dense municipal bus network under the name ESHOT. The name is derived from the E elektrik; S su (water); H havgazi (gas); O otobus (bus) and T trolybus. Electricity, water and gas are now supplied by separate undertakings and the trolleybuses ceased in 1992. The bus company has inherited the original name. ESHOT operates about 1,500 buses with a staff of 2,700. It has five garages at Karatas, Gumruk, Basmahane, Yesilyurt and Konak. A privately owned company, Izulas, operates 400 buses from two garages, running services under contract for ESHOT. These scheduled services are supplemented by privately-owned minibus or dolmuş services.

See also

The nine metropolitan districts of İzmir; namely, Balçova, Bornova, Buca, Çiğli, Gaziemir, Güzelbahçe, Karşıyaka, Konak and Narlıdere.

Alsancak; the business and luxury quarter in Konak

Kemeraltı; the historic bazaar zone in Konak

Levantine mansions of İzmir; 19th century Levantine houses in Bornova, Buca and Karşıyaka

Karataş; the traditional Jewish quarter in Konak

Yeşilova Höyük; the prehistoric settlement

Smyrna; the ancient city

İzmir International Fair

İzmir Economic Congress

Boyoz; a pastry very typical of İzmir

Occupation of İzmir

Great Fire of Smyrna

Alsancak; the business and luxury quarter in Konak

Kemeraltı; the historic bazaar zone in Konak

Levantine mansions of İzmir; 19th century Levantine houses in Bornova, Buca and Karşıyaka

Karataş; the traditional Jewish quarter in Konak

Yeşilova Höyük; the prehistoric settlement

Smyrna; the ancient city

İzmir International Fair

İzmir Economic Congress

Boyoz; a pastry very typical of İzmir

Occupation of İzmir

Great Fire of Smyrna